Single channel HD video

00:09:30

Camera assistance: Lydia Davies

3D modelling: Jay Mulholland

Watch: Site/Sight for GSA MFA’s GLUE

Closed captions: HERE

Awarded the Ivan Juritz Prize for Visual Arts 2021 (the Centre for Modern Literature and Culture at King’s College London and Cove Park) and the Postgraduate Chair’s Medal for Fine Art 2021 (Glasgow School of Art).

Read: ‘Genesis (what can’t light see?) restrospectively’, a retrospective accompaniment to the piece in Textual Practice Vol36.

00:09:30

Camera assistance: Lydia Davies

3D modelling: Jay Mulholland

Watch: Site/Sight for GSA MFA’s GLUE

Closed captions: HERE

Awarded the Ivan Juritz Prize for Visual Arts 2021 (the Centre for Modern Literature and Culture at King’s College London and Cove Park) and the Postgraduate Chair’s Medal for Fine Art 2021 (Glasgow School of Art).

Read: ‘Genesis (what can’t light see?) restrospectively’, a retrospective accompaniment to the piece in Textual Practice Vol36.

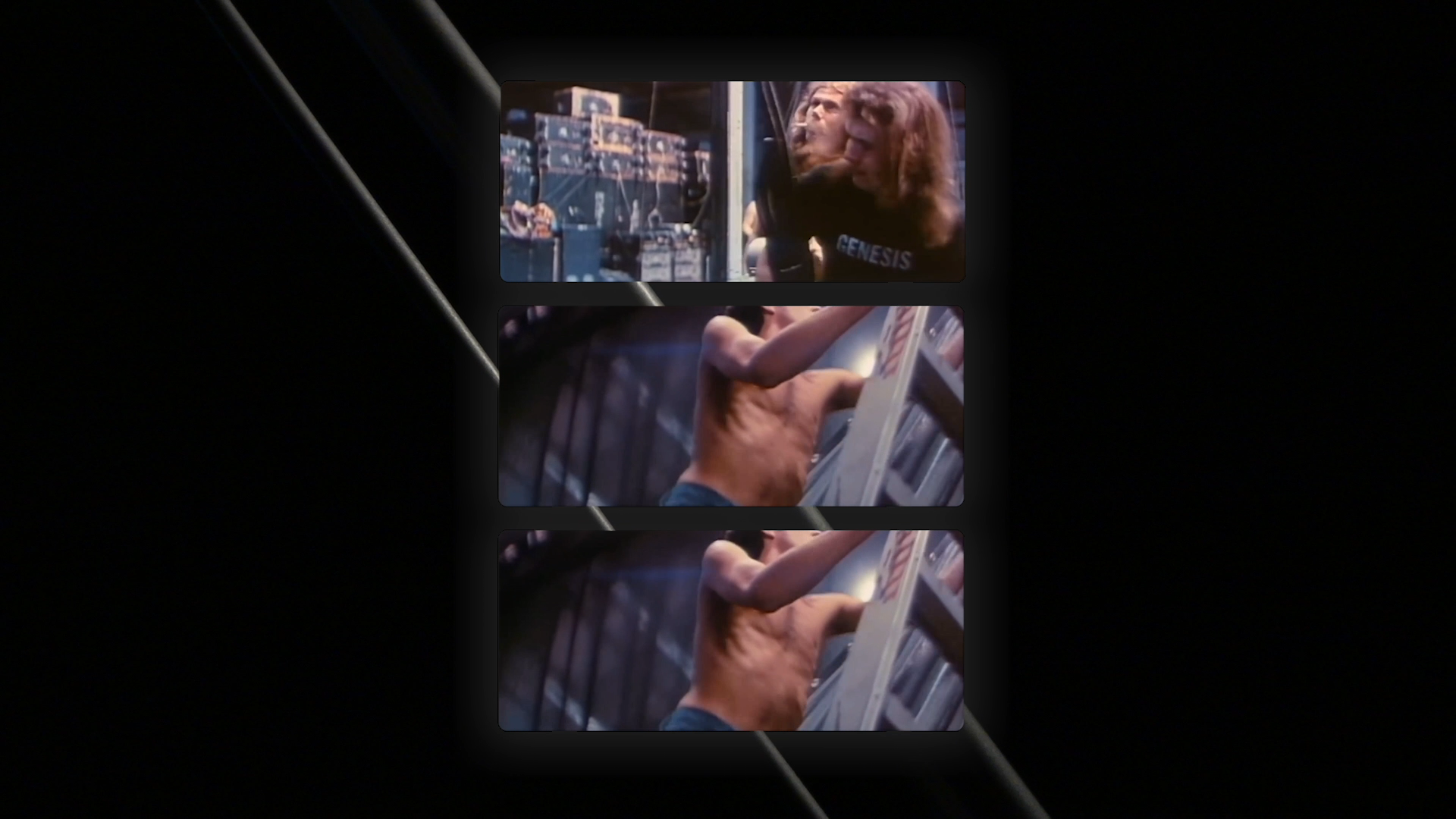

At music concerts, audio-visual nodes are designed to mirror and exacerbate both the plural ecstatic experiences of bodies and increasingly the technology attached to them. Here, collective and personal images, technological and human bodies, become confused. Inspired by an absurd and biblical story by Peter Gabriel, Genesis indulges in moments of ‘switch’ and explores our relationship to artificial light. The artefacts and appropriated characteristics of modernist design in the video form the edges of a world built on convoluted references, while the decidedly twee Englishness of Gabriel’s fable help reinvent electricity and light in moral terms. The wriggling motif of our friend the worm allows us to penetrate and embrace the darkness, emancipating our flesh from normative modern time, space and sensation.

“My heart still gives a little skip when I watch the film. Which is nice. Why?

Well – it’s dynamic in its combination of elements. It is described by the artist as variable in installation, but I think it is variable throughout itself, too, rewarding repeated viewings – the lot of the judge – with combinations of image and sound that wriggle and mutate each time. It leaves me space to watch it, despite the threat of the music, or the ‘fact’ of the band Genesis, becoming dominant. It is very hard to include recorded popular music in a short film or artwork, I think, without that musical artist’s work overwhelming the whole, but here the interruptions, and the changes – the literal ‘switches’ – the pauses and the gaps, the disjointed articulations, as well as the tracking between the senses of sight and sound, between reading and looking, refuse to let any overwhelming take place. Instead, we are confronted with overlaps, gaps, pauses, combinations, mechanics, emblems – and tensions.

What I most admire here is the awareness, the indication towards, the thinking through of parallel worlds. Key here is the world of the 1960s, where you call your band ‘Genesis’; a world full of fables of dubious natures, a reckoning with fables, a choice of a symbol of modern design – the Anglepoise – from which to extract an experiment, or to plot another path, or to try another body. A worm.

Things happen at different scales – I watch the round edged slides falling in leaves across the screen, either showing a lamp, or men working. I like how it gives me a ripple of eroticism, of homoeroticism, across the roadies installing; I am turned upside down with the crowd at the gig. Is the crowd at a gig here and now, or then and there, and how can I be there anyway – how can this be a film that is also of its time, our time if we are confined, at home with a lamp and screens, without announcing itself as such, and how does it turn its elements against themselves, too? … All these questions and more accompany my viewing.”

Well – it’s dynamic in its combination of elements. It is described by the artist as variable in installation, but I think it is variable throughout itself, too, rewarding repeated viewings – the lot of the judge – with combinations of image and sound that wriggle and mutate each time. It leaves me space to watch it, despite the threat of the music, or the ‘fact’ of the band Genesis, becoming dominant. It is very hard to include recorded popular music in a short film or artwork, I think, without that musical artist’s work overwhelming the whole, but here the interruptions, and the changes – the literal ‘switches’ – the pauses and the gaps, the disjointed articulations, as well as the tracking between the senses of sight and sound, between reading and looking, refuse to let any overwhelming take place. Instead, we are confronted with overlaps, gaps, pauses, combinations, mechanics, emblems – and tensions.

What I most admire here is the awareness, the indication towards, the thinking through of parallel worlds. Key here is the world of the 1960s, where you call your band ‘Genesis’; a world full of fables of dubious natures, a reckoning with fables, a choice of a symbol of modern design – the Anglepoise – from which to extract an experiment, or to plot another path, or to try another body. A worm.

Things happen at different scales – I watch the round edged slides falling in leaves across the screen, either showing a lamp, or men working. I like how it gives me a ripple of eroticism, of homoeroticism, across the roadies installing; I am turned upside down with the crowd at the gig. Is the crowd at a gig here and now, or then and there, and how can I be there anyway – how can this be a film that is also of its time, our time if we are confined, at home with a lamp and screens, without announcing itself as such, and how does it turn its elements against themselves, too? … All these questions and more accompany my viewing.”

-Josephine Pryde on Genesis (What Can’t Light See?)

for Textual Practice

for Textual Practice